Comparison between the archaeological remains of the Roman colonial center of Timgad and the Wari military center of Pikillacta will help us to explore how Imperial domination over colonial conquests was universally cemented through distinctive architecture and urban planning, designed to signify political control and organization.

With most Empires employing a ‘divide and conquer’ strategy,

architectural assimilation manifested the Empire’s commitment to a permanent

physical presence in their territories. Sites like Timgad and Pikillacta demonstrate

their respective Empire’s ability to establish monumental, intrusive centers

within culturally and spatially remote populations. Imperial control is reinforced through a uniform

representation of the resources, prestige and goods offered by the ruling

state—the Empire must represent a compelling image of what should be desired

and valued by the conquered society in order to promote co operation.

Hierarchal ideologies were intentionally incorporated into a

colony’s layout and buildings in order to sustain relations of dominance

between the Empire and its conquests. This transparent manipulation of space

imposes power structures which will further be explored and compared in our

case studies.

The respective archaeological sites demonstrate a universal argument for the controlled organization of colonial urban development. As evident from aerial views, both Empires applied an effort to manipulate the natural terrain of these colonies to adhere to a strict grid-plan. The manipulation of these foreign landscapes is consistent with the Imperial manipulation of its inhabitants through architectural medium. Traffic is controlled and regulated, hierarchal space is imposed, and iconographic ideals of the Empire manifests itself through a spatially organized power. It is through architectural assimilation and intimidation that the crucial unity of an Empire is preserved in its remote colonies.

The respective archaeological sites demonstrate a universal argument for the controlled organization of colonial urban development. As evident from aerial views, both Empires applied an effort to manipulate the natural terrain of these colonies to adhere to a strict grid-plan. The manipulation of these foreign landscapes is consistent with the Imperial manipulation of its inhabitants through architectural medium. Traffic is controlled and regulated, hierarchal space is imposed, and iconographic ideals of the Empire manifests itself through a spatially organized power. It is through architectural assimilation and intimidation that the crucial unity of an Empire is preserved in its remote colonies.

Timgad

Timgad was founded as a military colony by Roman Emperor

Trajan. The land was originally granted to veterans as compensation for years

of enduring harsh military service. Created ex

nihilo or ‘out of nothing,’ this site illustrates Roman urban planning at

its height: the square enclosure, with its strict orthogonal design and

perpendicular roads manipulates the elevated landscape to follow a precise grid

organization. The colony was

strong and prosperous, serving to maintain cultural dynamics and demonstrate Roman

ideals on African soil.

| ||||

Figure 1: Timgad Entrance, Algeria.

|

|

| Figure 2: Plan of Timgad, ~100 BC |

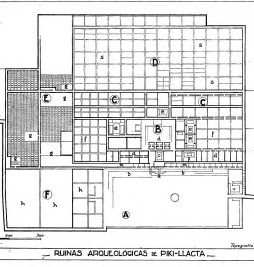

Pikillacta

This Wari military outpost is consistent with the Roman

necessity for military structures to have controlled and mathematical

organization. The various

provinces of the Wari Empire were protected by military instillations that

enforced power over local leaders, who were allowed to retain control of an

area if they agreed to join and obey the Wari Empire. The construction of large sites like Pikillacta marked a

threat of power to intimidate colonies.

This highly segregated space has various complementary sectors including

administration, ceremonial, roads and defense systems to impose aspects of Wari

socio-political hierarchies on external communities.

|

| Figure 3: Pikillacta, Interior. Wari manipulation of space to force specific routes and adhere to grid design. |

1. Hirst, Kris. “Andean Society call the Wari Empire,” Achaeology Sites and Places. http://archaeology.about.com/od/wterms/qt/wari_empire.htm

2. McEwan, Gordon. “Some Formal Correspondences between the Imperial Architecture of the Wari and Chimu Cultures of Ancient Peru.” Latin American

Antiquity. Society for American Archaeology, 1, 2 97-116, 1990.

2. McEwan, Gordon. “Some Formal Correspondences between the Imperial Architecture of the Wari and Chimu Cultures of Ancient Peru.” Latin American

Antiquity. Society for American Archaeology, 1, 2 97-116, 1990.

3. Schreiber, Katharina.

“Conquest and Consolidation: A Comparison of the Wari and Inka Occupations of a

Highland Peruvian Valley.” American

Antiquity, 52, 2, 266-284. 1987.

4. Thomas, Edmund. "Part I: Monumental Form." Monumentality and The Roman Empire: Architecture in the Antonine Age, Oxford University Press, 2007.

5. Tung, Tiffiny A.

“Violence and Rural Lifeways at Two Peripheral Wari Sites in the Majes Valley

of Southern Peru.” Andean Archeaology III.

435-467, 2006.

IMAGES

Figure 1: http://www.timgad-voyages.com/download/images/atv04.jpg

Figure 2: http://aureschaouia.free.fr/webgallerie/galleries/archive-algerie/plan-timgad2.jpeg

Figure 3: https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjonQBAYly86IR0_Av3LpnNGUh0LF0HA946HhN4fEt1hBOCjJ0HLfL8l0wCW_3YEWWjahS3JYURktjgiJmLefomVw38LQhAZoXtrafkQNIx0lSA_EEat6_x4rcTcSos4PeJZUfvAUJIdBY/s1600/pikillacta02-1.JPG

Figure 4: https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhXx5jiun4uuYD4G86QavbWaz9a-BZnUsAZxw82sd9COPKVGIlJ2oE-BTUbjbW72UmBEdza_CJWAX02ugkrMN2VUCgl1_PMNXKFDvloB63eZOWZUCDQV7okf5icPuFKRkji1g0XD2A6wNpI/s1600/2.17timgad.jpg